Every year in mid-October, I travel to Puglia with my groups. My local guide friend, Giusy, joins me for part of the program, and over the years we've developed a few rituals for our free time.

In Bari, we always stop at Bar San Nicola for Tette delle Monache — my favourite Puglian dessert. In Lecce, we enjoy a Caffè Leccese on Piazza Sant'Oronzo, and in Ostuni we order the same panino every time, filled with prosciutto, mozzarella, and sun-dried tomatoes. While we enjoy our sandwiches at the little corner shop, we chat about tourism trends in Puglia, our families, or our off-season travels outside Italy.

The shop sells only local, high-quality products: cheeses, pasta, wine, biscuits, and, of course, olive oil. This year, some people in my group were disappointed because the shop had run out of oil. The owners refused to sell last year's stock; they were already waiting for the new season's oil: il novello.

We're lucky because every November we can get our family's supply of olio nuovo straight from the frantoio (olive mill). We don’t have our own olive trees, but over the years we’ve found excellent sources of oil in several regions: Puglia, Campania (Cilento), Tuscany, and Liguria.

These past years we spent the first days of November in Cilento, guiding our Cilento Slow Tour. One of the highlights of this tour is the chance to see an olive harvest, followed by a visit to the frantoio and a lazy lunch at the farm.

We never know exactly where we're heading, because Serena, who runs the olive mill, sends us the coordinates only on the morning of the harvest. This year we found ourselves in an absolutely stunning location: a vast olive grove surrounded by steep green hills and three hilltop villages perched on the ridges. Silver-green leaves shimmered in the morning light, trunks twisted like dancers, and nets were neatly spread beneath the branches. But behind this annual ritual lies a story as old as Mediterranean civilization itself.

From the Eastern Mediterranean to Italy: the journey of the olive tree

The olive tree (Olea europaea) is among the oldest cultivated plants on earth, first domesticated 6,000–8,000 years ago in the Eastern Mediterranean — in the lands that are now Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and Cyprus. From there, the Phoenicians, famous for their seafaring trade networks, spread olive cultivation westward to North Africa and Greece. Olive oil was already being produced in some of these regions as early as 5,000 B.C.

Greek settlers were the first to introduce olive trees to Southern Italy, planting them in what are now Calabria, Puglia, and Sicily. The Romans later expanded these groves across the peninsula, valuing olive oil not only as a food staple but also for healing, lighting lamps, caring for skin, and even as a form of payment. By the height of the Roman Empire, Italy had become a major Mediterranean center for olive cultivation — a reputation it still enjoys today.

Throughout history, the olive tree has carried deep cultural and symbolic meaning: it represented peace and well-being, Homer famously called olive oil "liquid gold", Olympic champions were crowned with olive branches, and in the Bible, the dove returning to Noah's ark carried an olive leaf.

Life in the grove: a slow traveler's view of the harvest

While we only spent a few hours in the grove, local farmers work for long days to pick the olives. Everyone has a few olive trees, or has a family member or friend who produces enough oil to share.

It is extremely important to watch the olives carefully as they shift from bright green to a darker violet-black, and to choose the right moment for the harvest. Large nets are spread under each tree to catch the fruit. In traditional groves on steep terraces, nets are carefully arranged among rocks and ancient roots. While we enjoyed harvesting on easy terrain, a local man explained to us how exhausting it is to work on the steep hillsides of Cilento. It's a truly demanding physical job.

Farmers hit the upper branches with a stick or use a small machine with a propeller-like end to shake the fruit off the tree. We all tried it and quickly realized that holding this machine overhead for just a few minutes is quite a workout. On lower branches the fruits are picked by hand or with the help of a small plastic rake.

The olives fall onto the nets, and from there they are collected into crates. They are usually taken to the frantoio within 12–24 hours.

Inside the frantoio: where the magic happens

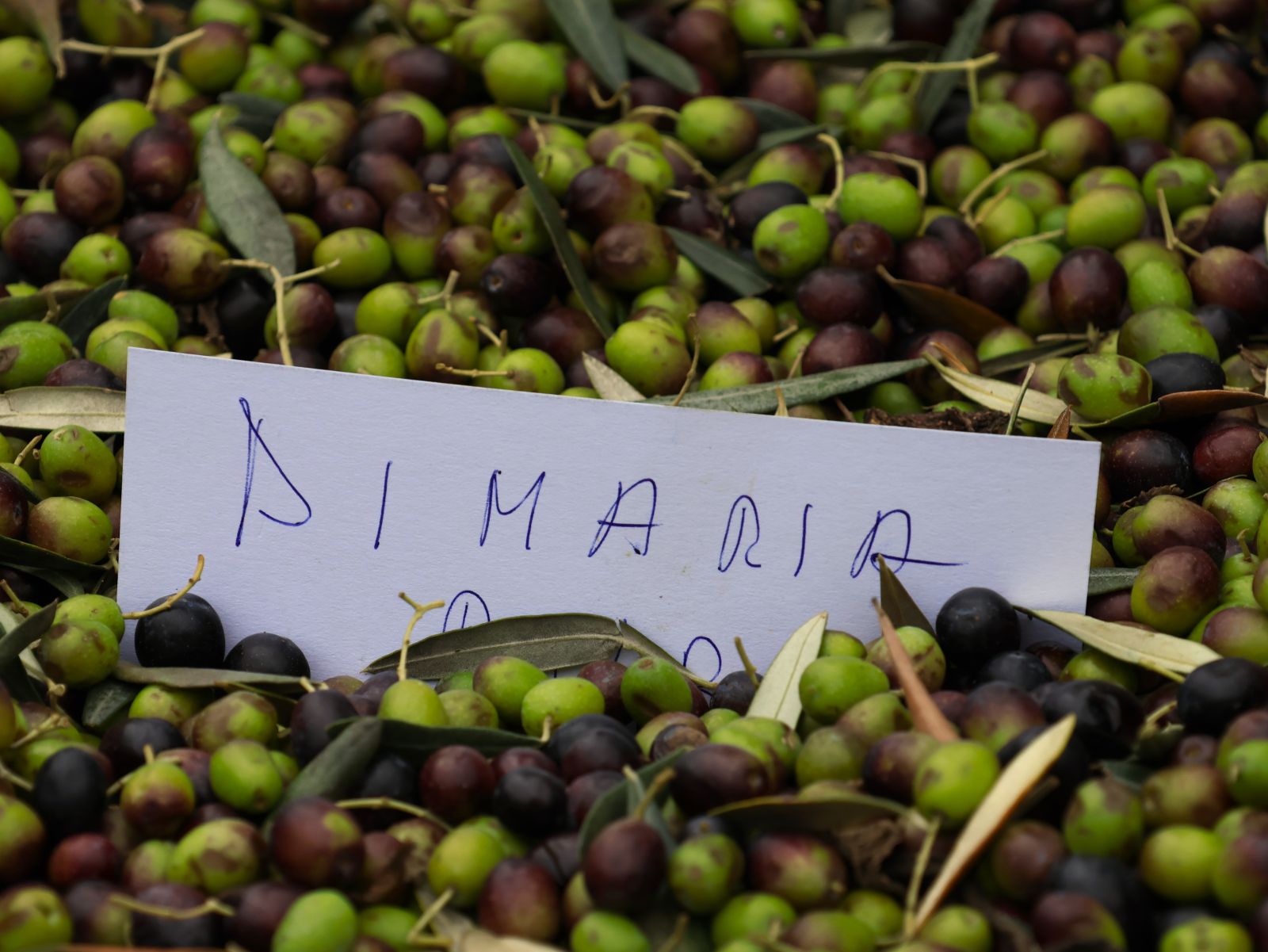

The frantoio isn't just a mill: it's the beating heart of harvest season. Farmers arrive with crates and sacks of olives, their names written on a piece of paper and stuck between the fruits.

Every farmer books a time slot at the mill and pays roughly €15–22 per 100 kg of olives. Since the harvested fruit still contains leaves, the first step is to blow them away. After a thorough wash, the olives are ground into a paste, pits included. A centrifuge then separates the oil from the pulp. To qualify as extra virgin, the oil must be extracted mechanically and kept below 27°C.

Some mills are now experimenting with making oil without the pits. We had the chance to taste such an olive oil in Puglia, near Cisternino. It had a pleasant, light flavour, though I personally prefer stronger, spicier oils.

A ritual that shapes communities

When the fresh extra virgin olive oil appears, the owner of the oil has the right to taste it first. It's a very important moment — they simply dip a finger into the stream. The farmer then takes home the olio nuovo, and the family tastes it immediately with bruschetta.

While the taste of the oil lasts all year, the flavour of freshly pressed olive oil is incomparable — intense, vibrant. It’s pure magic. To me, this fruity and spicy taste is quite addictive: on days, when I work from home, I often have a very simple lunch: fresh bread, olive oil from Cilento or Puglia, tomatoes and a pinch of salt. A bottle of high quality olive oil is also a regular gift to our family and friends.

For many Italian families, the olive harvest is more than agriculture; it’s a cultural anchor. Relatives return home to help pick the fruit. Children play beneath trees their great-grandparents planted. The shared meal after a day's work is a celebration of the land and its rhythms.

As a slow traveler, being present for the harvest feels like slipping into an older, more patient Mediterranean world. It’s a reminder that good things — especially good olive oil — cannot be rushed.

Thinking about planning a trip for the olive harvest season?

If you would like to experience the olive harvest, plan your trip for October or November. The colours and lights are beautiful at this time of year, and with some luck, you'll enjoy warm autumn weather. This year, we were swimming in the sea on November 4! In late autumn you'll find hardly any tourists in the villages of Cilento, and accommodation prices are at their lowest, so it's a wonderful time to travel anyway.

Last year we also made a short video about the olive harvest in Cilento:

Many years ago, I visited the olive harvest in Tuscany and Cinque Terre with two journalist friends, and we created this video:

As always, thank you for reading!